What Is a Good Monthly and Annual Churn Rate for a SaaS Company?

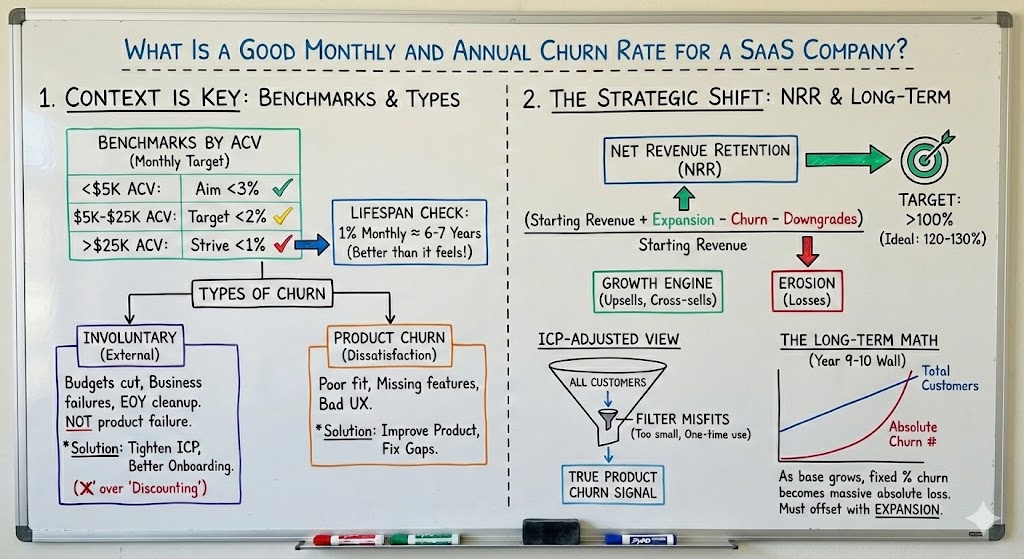

A practical guide to SaaS churn benchmarks by ACV, how to interpret churn spikes without panic, why NRR matters more than logo churn, and the retention levers founders can pull as their customer base grows and churn becomes a bigger headwind.

Churn is one of those SaaS topics that seems straightforward until you actually have to manage it at scale. The math itself is simple. The emotional experience of watching customers leave is not. And the hardest part is that churn isn’t a single thing—it’s a bunch of different dynamics bundled into one number that can make you feel brilliant one month and deeply concerned the next.

In our SaaS CEO mastermind, the conversation started the way these discussions often do: with someone wondering whether what they were seeing was unique to their business. One founder asked it directly:

“Are people seeing elevated levels of churn? We’ve seen higher onboarding churn over the last six months. It started around December and continued into January, about 10% higher than last year.”

That pattern isn’t unusual. We’ve seen churn creep up across mid-market SaaS near the end of the year, then stay elevated into early Q1. The key is not to panic, but also not to dismiss it. You want clarity on what “good” actually looks like for your ACV tier, what’s driving the churn you’re seeing, and which levers you can realistically pull to influence it.

First: “Good” Churn Depends Heavily on Your ACV

One of the most common mistakes founders make is comparing their churn to benchmarks that don’t apply to their business model. A $49/month self-serve product and a $25K ACV mid-market platform with an onboarding process live in completely different churn realities.

In the mastermind, we shared practical benchmark ranges by ACV to ground the conversation:

- Under $5K ACV: aim for under ~3% monthly churn

- $5K–$25K ACV: target under ~2% monthly churn (roughly <25% annually)

- Over $25K ACV: strive for under ~1% monthly churn

These aren’t laws of physics, but they’re useful sanity checks.

.jpg)

For the specific case that sparked the discussion—mid-market SaaS in the $10K–$15K ACV range—we talked about how 10–15% annual churn (roughly 1–1.5% monthly) isn’t automatically bad. In fact, when you translate churn into customer lifespan, it often looks healthier than it feels emotionally.

One line from the discussion captured this clearly:

“For a mid-market firm at about $10–15K ACV, a good target would be under 25% annual churn, under 2% monthly churn. At around 1% monthly churn, your average customer stays six to seven years. That’s actually better than normal.”

When you frame churn in terms of customer lifetime instead of just loss, your brain tends to calm down. A 1% monthly churn rate and a 4% monthly churn rate might both sound like “single digits,” but they imply radically different businesses underneath.

Second: Separate Involuntary Churn From Product Churn

One reason churn gets psychologically messy is that we instinctively treat it as a referendum on product quality. Sometimes that’s true. Often, it isn’t.

In the mastermind, a meaningful portion of the churn being discussed wasn’t driven by dissatisfaction with the product. It was driven by external realities: businesses closing, budgets being cut, non-profits losing funding, or companies doing end-of-year subscription cleanup.

One CEO described the seasonal pattern clearly:

“Our churn was actually going down right up until November. Then it ticked up in November and spiked in December. It’s come back down in January. It felt like end-of-year cleanup, where people were reviewing subscriptions and shutting things off.”

Another founder shared a harder version of the same theme:

“It’s mostly older customers churning. They’ve been with us three or four years. Some of them are large non-profits that have had budgets cut. We tried discounting heavily—50% off—and still couldn’t keep them because they were shutting down.”

That’s an important reality check. If churn is driven by involuntary factors, aggressive discounting often doesn’t solve the problem. In those cases, better levers might include:

- Tightening your ICP and qualification earlier

- Improving onboarding so misfit customers don’t activate in the first place

- Building expansion revenue so net retention stays strong even when some logos churn for reasons outside your control

Not all churn is fixable, and treating it as such can distract you from the changes that actually matter.

Third: Track Churn, but Run the Business on Net Revenue Retention

If you only look at logo churn or gross revenue churn, you’re missing the full picture. The metric that really tells you whether your SaaS business is compounding or eroding is Net Revenue Retention (NRR), because it captures both sides of the equation: what you lose through churn and downgrades, and what you gain through expansion.

In the discussion, we emphasized tracking NRR alongside churn and being intentional about driving growth through the existing customer base. For mid-market SaaS, targeting something like 20–30% growth via NRR was mentioned as a meaningful strategic goal.

.jpg)

This is also where Customer Success stops being just a support function and becomes a growth engine. In the program materials, we talk about aligning CS around NRR, tracking it visibly, and compensating the team on it. NRR is the clearest signal of whether your customer base is strengthening over time.

Fourth: Use ICP-Adjusted Churn So You Don’t Lie to Yourself

There’s a subtle churn trap that catches a lot of growing SaaS companies. If you sell to everyone, your churn might look “bad” even if your product is strong, because you’re accumulating customers who were never likely to stick around.

That’s why we discussed ICP-adjusted churn as a way to interpret reality more honestly.

The idea is straightforward: define your retention ICP, then separate out customers who were structurally likely to churn. That might include:

- Very small companies in volatile markets

- Customers using the product for a one-time project

- Accounts that never completed onboarding properly

When you do this, you can distinguish between a product problem and a targeting problem. That distinction matters, because the fixes are very different.

Fifth: The Hard Math of Churn Shows Up Around Year 9 or 10

Even if your churn rate stays stable, the absolute number of customers churning grows as your base grows. Eventually, churn becomes a headwind you’re racing every month. This transition tends to sneak up on teams and is one of the harder moments in SaaS scaling.

We talked about this explicitly in the mastermind. One founder described it this way:

“There’s a math that kicks in. Churn is a percentage that grows with your base. After a while, that percentage becomes the difference between net new logos and churn. It happened to us around year nine. We stopped adding customers faster than we were losing them, because the percentage of a much bigger number is still a big number.”

This is why long-term SaaS winners obsess over two things simultaneously: keeping churn low and predictable, and driving expansion so NRR offsets a meaningful portion of churn. The earlier you build those muscles, the less painful this phase becomes.

So What’s “Good” Churn, Really?

A founder-friendly answer is that “good churn” is the level of churn where your unit economics and growth strategy still work, and where the churn is explainable.

For many mid-market SaaS companies, under ~2% monthly churn and under ~25% annual churn is a healthy target range, with the understanding that short-term spikes—especially from November through January—are often driven by budget cycles and subscription cleanup rather than product failure.

The best operators don’t stop at the number itself. They ask deeper questions. Is the churn involuntary or product-driven? Is it concentrated in non-ICP segments? Are we driving enough expansion to keep NRR strong? And are we prepared for the reality that churn becomes a bigger absolute headwind as the company matures?

That’s the real game. Churn is a metric. Retention is a strategy. And in SaaS, retention strategy is one of the most reliable ways to turn a good business into a compounding one.